For a neutral observer, this year’s Gulf Cup could hardly have offered a more tempting final menu. Two sides with monstrous chips on their shoulders battling it out until the very last second of the added time.

The Saudi final curse has been well-documented, but just in case you haven’t taken note – this was their fifth significant heartbreak in the last 12 years, four of them on this very stage, one more in the 2007 Asian Cup final.

On Sunday, Saudi hearts started crackling sooner than usual; Salem Al-Dawsari hit the crossbar right off the bat with Salman Al-Faraj soon tagging the woodwork from the penalty spot as well. They never recovered.

Bahrain, too, have enjoyed their own share of near-successes.

In 1982 and 2003, they came just one point short. But theirs was actually a story of big modern-era underachievers. Since the knock-out stage was introduced in 2004, they’ve not made a single final, and that’s throughout pretty much the entirety of international careers of Ismail Abdulatif and Faouzi Aaish, as well as the whole peak of Mohamed Salmeen.

This year turned out to be Bahrain’s time.

Having waited for almost half a century, they finally clinched their maiden Gulf Cup title. And you know what? Good on them! It was nice to chalk off one missing regional title in August (WAFF Championship), but the Gulf Cup is still a different animal of a competition in comparison to the much younger, decidedly B-grade WAFF Championship.

So how did Bahrain make it, and how did Saudi Arabia manage to end up empty-handed yet again?

Hélio Sousa stamps his spectacular 2019

It’s becoming clear that if any Asian nation wants to make an immediate splash, it better go hire a Portuguese-speaking coach. Mário Zagallo famously took Kuwait to the 1976 Asian Cup final (the country’s second ever appearance, no less) a mere few weeks into his two-year tenure, while Jorvan Vieira wasted no time in Iraq, taking them to the WAFF Championship final and, of course, the biggest of all – winning the 2007 Asian Cup.

Both of these instant impacts have interesting back stories – Iraqi players were ready to pay out half of Vieira’s contract to see him go just before the historic tournament, while Zagallo had won three World Cups before finally growing bored with Brazil and venturing into Middle East to prove himself further.

Hélio Sousa might still be the most peculiar case study, however. Having only coached youth national teams, and two smaller clubs in his home country, he was far from an established name and some even may have expressed their doubts when he took a break to lead Portugal U20 in the summer World Cup.

Half a year later, Bahrain have conquered two tournaments they’d never won prior to 2019.

Better yet, Hélio Sousa “solved” the Gulf Cup by averaging 11 line-up changes each matchday. That’s right. Usually, going through an exhausting extra time in the semi-final would be a nuissance, a complication, but not so much for Bahrain, since a wholly different line-up had already been named to start the final a few days later.

And here we were, thinking Saudi Arabia’s depth is insane. Bahrain won this tournament with a goalkeeper wearing the captain’s armband despite sitting the first two games out, how about that?

No need to start firing on all cylinders. Not even one, frankly

The UAE of 2013, powered by peaking tandem of Omar Abdulrahman and Ali Mabkhout, remain the last Gulf Cup champions who were legitimately scary from the get go, exploding out of the blocks with five goals in the first two games.

That, in isolation, would hardly be a stunning finding – this was only the third edition since 2013, after all.

What’s more fun is when you realize how consistently odd – or oddly consistent – the Gulf Cup has lately been with slow starts of eventual champions.

At the 22nd edition, Qatar stumbled out of the gate to three draws and wildly unimpressive progression fueled by a single goal from defender Ibrahim Majid.

A few years down the line, Oman looked determined to follow up on Qatar by also not bagging a single goal from open play in the group stages, only to prove unable to hold their horses in the Matchday 3 upset of Saudi Arabia.

In 2019, Bahrain remained goalless for two first games, only to suddenly deliver six blows over the next two games.

This is just weird. Just like it was weird (if understandable, given their Champions League exploits) to see Saudi Arabia line-up without a single Al Hilal player in their opening starting XI. And it’s frankly no less weird to now acknowledge that this year’s finalists combined for a single point in their opening showdowns at the tournament, something that’d never happened before (only in 2009, both finalists didn’t win initially).

Amid another heartbreak, Saudi Arabia find their face

Hervé Renard may want to think about changing his famously stubborn ways; his token white shirt that made him the first coach to win Africa Cup of Nations with two different countries seems to be no longer working.

First, there were the impressive performances that translated into a mere point at 2018 FIFA World Cup. Then there was the disappointing Round of 16 exit at this year’s AFCON, and now this. Against Benin, much like now against Bahrain, he was let down by his penalty taker and then some more bad luck, too.

Yet, while he’ll always have his favourite shirt and his favourite individuals, he’s no stubborn tactician.

If his predecessor Juan Antonio Pizzi came in with a clear vision he was unwilling to drop even as it was becoming painfully obvious the plan to build from the back doesn’t fit the personnel, Hervé Renard is the polar opposite; a professional chameleon.

The Frenchman doesn’t have his preferred formation, nothing like that – he seeks one wherever he goes.

It’s worth remembering that Renard won his first AFCON gold with a direct, counter-attacking Zambian outfit while deploying a purely defensive-minded central midfield in 4-4-2, then he enjoyed a brief period of success at Sochaux with a classic 4-2-3-1, and finally found the one fitting formation for underachieving Côte d’Ivoire.

In a peculiar 3-4-3, Yaya Touré played the deepest he’s ever operated for the national team, which seemed counter-intuitive at the time, but it was designed to unleash the devastating wide players.

It worked a treat, of course, and Saudi Arabia seem to be morphing into a similar monster.

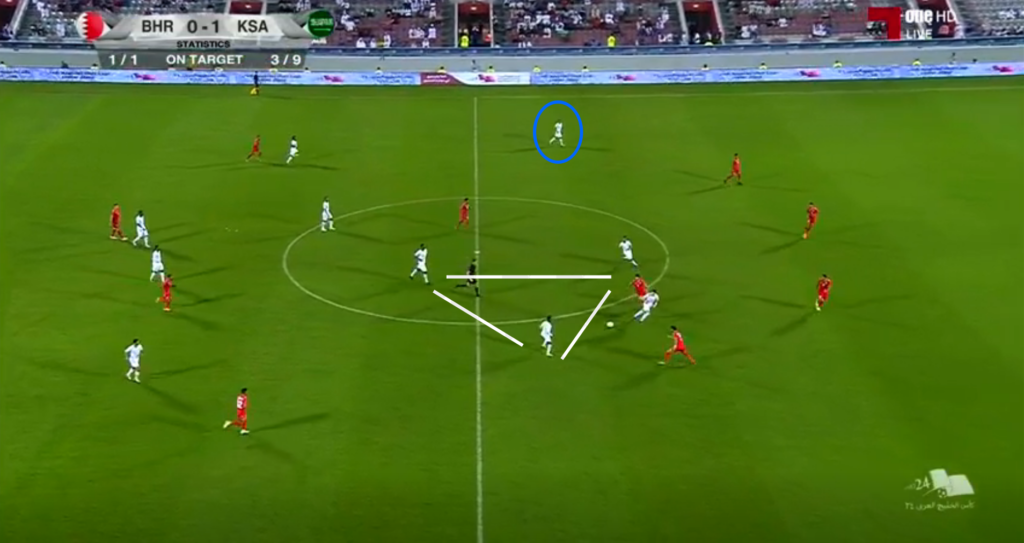

Fawaz Al Qarni is installed in goal as he doesn’t mind playing a longer ground pass to accelerate build-up down the middle. Abdullah Otayf is now the prototypical libero of the side, dropping deep to distribute smoothly to the flanks or, alternatively, free up the right centre back Mohammed Al Khabrani for a diagonal to the left-hand side. Salman Al Faraj is suddenly seen as the most advanced central midfielder, a roaming presence around the box.

It took some time, but Renard has seemingly figured out how he wants his team to set up and attack. The attacking can be done patiently as well as quickly, or both at the same time, to a devastating effect.

Everything is now focused towards one goal: activate the wide areas and exploit the half-spaces through underlapping runs of a fullback, or smart movement of midfielders / inverted wingers.

Half-spaces that are notoriously hard to defend, mind, especially with Yasser Al Shahrani-Salem Al Dawsari / Sultan Al Ghanam-Nawaf Al Abed clicking.

Bahrain had learnt it the hard way in their first encounter when both winger-fullback pairs ranked as the top passing links for Saudi Arabia. That’s always going to be great news with the aforementioned mindset. Crucially, lone striker Abdullah Al-Hamdan has bought in as well, popping up on the wide left channel.

After some worryingly pedestrian performances early on in the World Cup qualifiers, Saudi Arabia are now playing with purpose, direction and concord. There’s never a couple of teammates too far away from one another.

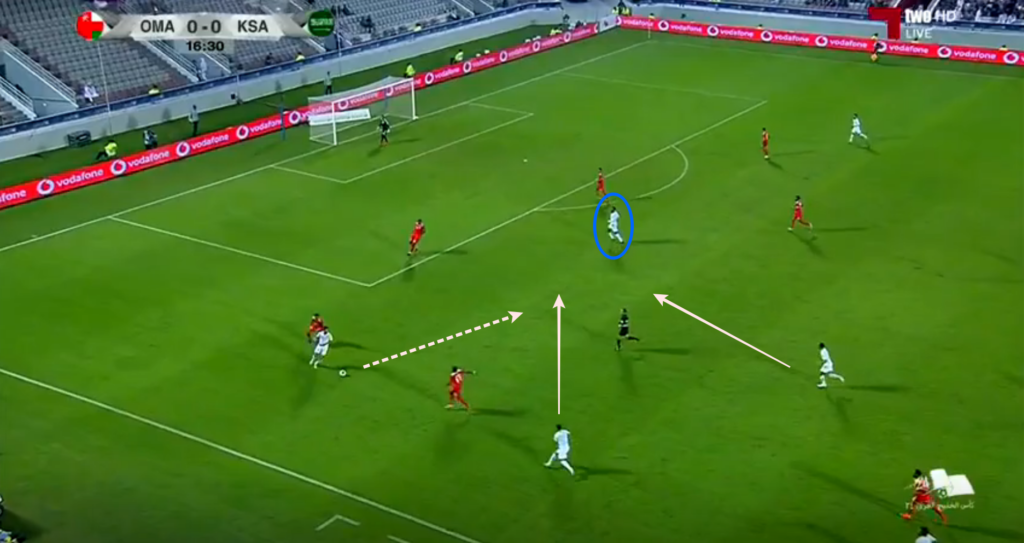

And this – Saudi Arabia finding their functional communication channels – is what matters here above all. Just look below at how Saudis were consistently able to move the ball from side to side with the necessary swiftness and some welcome guile on top.

They basically move the ball horizontally while opening up free pockets, and thus virtually advancing the play at the same time; keeping the opponent on their toes.

A Gulf Cup curse might be as real as ever, but Renard wasn’t hired for that. We should more eagerly focus on the two shots on target allowed to Qatar and the refreshingly activated wing play (with a refreshingly fit Al Abed, especially) in their other games – a likely blueprint for the future – rather than the one final heartbreak.