Asian football has changed, that much we know.

Kawasaki Frontale’s AFC Champions League Elite semi-final against Al Nassr on Wednesday will tell us by how much it has changed.

The opening days of what is being called the AFC Champions League Elite Finals 2025, held for the first time (outside of COVID) in a centralised location, have laid bare the degree to which Asian club football is now dominated by Saudi Arabia.

The victories by Al Hilal, Al Ahli and Al Nassr were as brutal and ruthless as they were instructive. Against some of the best teams from this year’s East Zone, the Saudi Pro League clubs won by an aggregate of 14-1.

It has alarm bells ringing everywhere, although there are mitigations.

Gwangju, for all their improvement in recent years, are still one of the most modestly operated Korean clubs and far from being a powerhouse that you’d expect can compete at this level. Only as recently as 2022 they were playing in K2, the second tier in Korea, and finished ninth last season, 25 points off top spot and only five above the relegation zone.

Buriram United, despite being the standard bearer for Southeast Asia, is still short of the best teams from the East Zone even if they’ve shown they can compete at that level.

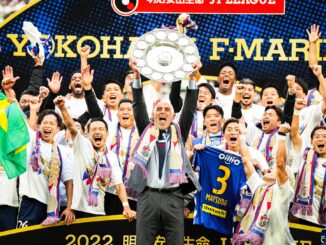

Yokohama F.Marinos are the outlier, as they have in recent times been one of the strongest Japanese teams and theoretically should have been able to muster a more resilient performance than what they managed.

But they arrived in Jeddah in the midst of their own crisis, sitting last on the J. League table with just one win from 12 this season and just days after Steve Holland was sacked. This was a team in turmoil, and it reflected in their performance.

So while the performances and results sounded a warning, it was not a case of the best of the West against the best of the East. These are good teams, but far from the strongest that East Asia has to offer, while the three Saudi clubs are by far some of the strongest from the other side of the continent.

There are myriad reasons for that – the demise of Chinese football, the stronger competitive balance in Japan and Korea – that are worth exploring in depth in the future, and how they will shape the conversation around Asian football going forward.

This year, though, Kawasaki Frontale stand as the last hope of the East against the impending (and inevitable?) tidal wave from the West.

Speaking on The Asian Game Podcast before this mini-tournament began, Scott McIntyre explained why Kawasaki were perhaps the best chance to succeed of the four clubs from the East Zone.

“I think they’re probably in a bit better position to do better than Marinos are,” he said.

“They’re well organised. They’re hard to break down, and they’ve still got enough creativity in Marcinho and (Akihiro) Ienaga.

“It’s great to see this team, although it doesn’t really resemble the one that was at the height of its powers three or four years ago, but it’s great to see Kawasaki, who were one of the dominant Japanese teams of the modern era, finally getting a chance to go on to this stage and show what they can do.

“They have the players to cause danger, and they have the organisation as a team, a real unity and a cohesion and a mixture of veterans and younger players. I think they’ve got the elements there, and if there was going to be a team that wins it, maybe outside of one of the Saudi clubs, I think it could well be Frontale.”

That organisation and collective strength were on display as they finally found a way past Al Sadd in the most competitive of the quarter-final ties.

Twice Kawasaki took the lead in regulation time, and twice Al Sadd pegged them back. Yasuto Wakizaka’s broke the resistance of the Qatari side and Kawasaki saw their way through to a semi-final with Al Nassr, featuring the likes of Cristiano Ronald and Jhon Duran.

“It was a hard game for us,” Frontale’s French-Japanese goalkeeper, Louis Yamaguchi, told The Asian Game after the game.

“We scored first, and then we got scored against a few moments after that. So it was a difficult game, but the motivation of the team was really superior compared to the results of what the opponent did; always, they came back and came back. But the team was really motivated, and we scored the last goal. So it was really nice.

“Defensively, we have a lot of things to look at. Me, firstly, on the first goal, it was a mistake of mine. But after that, I changed my mind and focused on what was coming next. So I forgot (about) that mistake, and kept playing the game and being on my best performance.”

Having cleared the first hurdle and made the semi-finals for the first time in the club’s history, Yamaguchi and his teammates are now targeting silverware.

“It’s something historical for the club and for the team,” 26-year-old Yamaguchi said.

So we don’t want to stop here. We want to go all the way and be champions.”

To do that they first need to overcome the might of Al Nassr, who are in their third semi-final in the past five seasons. The whole team will need to be at their best if they are to overcome the odds against Al Nassr on Wednesday.

Before this year, for the past decade the only time teams from Japan and Saudi Arabia could meet was in the final, which is what happened in 2017, 2019 and 2022 when Urawa Reds and Al Hilal faced off in a trio of iconic finals.

Despite, even at that point, Al Hilal having more pulling power to attract a higher calibre of foreign talent, Urawa were able to more than hold their own, winning two of the three titles, while the ledger across the six matches reads two wins apiece and two draws.

The contrasting styles between Japanese and Saudi football has always been a compelling element of these fixtures, and it’s here that Japanese teams have often had it over their Saudi counterparts.

“In West Asia we’ve always respected Japanese teams,” Saudi-based content creator Mohammed Fayad explained on The Asian Game Podcast last month, “because no matter what foreigners the Saudi teams or the Qatari teams or the Emirati teams have had, the Japanese sides have always held their own.

“Because one thing that is a general theme about Japanese football in West Asia is that they actually have a healthy football system, and so if they have foreigners like the Saudi league, we’d actually be so much more scared, like for our lives.

“Because imagine them with their good systems, with their competitive leagues, with their good fan bases, and then some crazy foreign players, right? So I think it’s always going to be close, and when it comes to knockout games, it’s going to be different.”

It’s worth remembering, however, the last fixture between the two nations came in the 2022 final between Urawa Reds and Al Hilal, won on that occasion by the Japanese side. Notably, that was before the recent surge of investment in Saudi football which has so distorted the natural order.

It’s also the first time since the competition was reformed which, importantly for this discussion, included a loosening of restrictions on foreign talent. Previously clubs were limited to the old 3+1 restriction, which was increased to 5+1 for the 2023-24 edition, which tended to favour those with a strong domestic core.

Under the new format of the competition, the restriction on foreign players has been removed entirely, with clubs now able to field whatever their domestic regulations allow, which significantly favours clubs with deeper pockets, in particular those from Saudi Arabia, but also clubs like Buriram United and Johor Darul Ta’zim in the East that often fielded sides comprised almost entirely of foreign players.

How J. League teams, which are increasingly seeing their best local talent move abroad at an earlier age, are able to compete against this new world order remains to be seen.

“The level in Asia is growing, especially in Saudi Arabia,” J. League Football Director Osamu Adachi said in an interview last year on the J.League’s official YouTube channel.

“They’re putting a lot of effort into recruiting foreign talent and we as the J. League have to play against them. But I think that we can challenge them with Japanese players, we can conquer Asia by leveling up Japanese players.

“I think it’s OK if clubs want to build a team around foreign talent if we got rid of the quota, but the core of the J. League is so that the national team can win against the world, it’s to win in the World Cup, it’s to raise competitiveness and to contribute locally, that’s the J. League.

“If we do that, Japanese players will grow. And if we want growth I don’t think we need to change the foreign quota, if anything I think we can even reduce it.”

Japanese clubs being able to conquer Asia with largely domestic squads has been the case in the past, whether it remains so is the question we are about to have answered when Kawasaki face the might of Al Nassr.

The starting XI of the Saudi side against Yokohama F.Marinos featured seven foreign players, with another two coming off the bench. The Kawasaki side that defeated Al Sadd, meanwhile, featured just two with all five substitutes also being local Japanese players.

The heavy loss of Marinos to Al Nassr is somewhat foreboding. How Kawasaki fare will lay bare just how much this week has changed Asian football.

Photos: Asian Football Confederation & Al Nassr

Note: Translation for quotes from J. League Football Director Osamu Adachi provided by @j_football_now on X

Listen to Episode 243 of The Asian Game Podcast as we preview the AFC Champions League Elite Finals.